Since I often write about the places I have lived, I thought it was a good idea to write about the two and a half years I spent in Lancaster, UK. This entry touches on the highs and lows of this period of life, without mentioning any names or too much detail. I am prepared for some of these comments to annoy a few academics (some of whom probably deserved it, some not) and townsfolk, or to be taken locally as criticisms from a ‘Southerner’ who resided fleetingly in the North of England. But although I grew up in London, I spent most of my adult life outside the UK. These days I am actually 16,000km south, in Melbourne Australia. And, for those academics still in search of a paying job, I probably seem very lucky.

From Jan 2017 to June 2019 I was based in Lancaster UK, as a Professor at Lancaster University. For someone who is slow to embrace change in middle age, this was a big move. I had spent the previous 14 years teaching in Melbourne, Australia, own a house there, and we (my wife, son and I) were well settled. The last time I had worked full time in the UK was in 2001, when I left the London School of Economics to work in Tucson, Arizona. I did, however grow up in the UK, and I have parents, sister, and nephews there.

I attended a job interview in Lancaster in January 2016, in the middle of a cold winter. The city was recovering from a major flood a month and a half earlier, that took out the electricity substation and plunged parts of the city, and the University, into darkness until temporary generators were installed by the Army. Having not seen my father for a while, he joined me in Lancaster and we looked around the city. Evidence of the flood was patchy, and we enjoyed the city with its shopping streets arranged in a cross, surrounded by the ring road that partly follows old city walls. Lancaster Castle has an interesting history [starting as a Roman fort, then built over, hosting the Pendle Witch trials in 1612, a women’s prison until 2011, a courtroom, etc. ] and the oldest streets, and the Priory, surround it. Much earlier, this city featured in the ‘War of the Roses’ – the House of Lancaster was associated with a red rose, and the House of York, a white one. They battled roughly between 1455 and 1487. Apparently there are echoes in the drama series Game of Thrones, which I have never watched. To the east Williamson Park was stunning with its views west over the Lake District [photos below], the rather-too-close nuclear power station at Heysham, and masses of maritime wind turbines were visible stretching from Barrow to North Wales. The park, the Priory and Castle, and a few other historic buildings suggested a level of past affluence [Baron Ashton who commissioned the park, had wealth from manufacturing]. Lancaster was also the ‘4th port’ in Britain’s triangular slave trade with West Africa and the Americas. The city was cold – this was January – despite the maritime position, only 5km from the west coast of England.

Lancaster University does not have such a long heritage. It dates from the late 1960s on its site 4km to the south of town, without a train station, and it is often viewed only by people passing north and south on the M6 motorway or by train. During my interview we stayed just off campus. It was the same campus I had once visited in 1981, when I was retaking my Geography A level at a crammer college in London, and at that time Lancaster offered me a conditional place on a geography undergrad degree. I did not take it up. The professor who interviewed me back then had, understandably, retired by 2016 (although I got to know him recently). The campus is on a hill, accessed via a cycle path that takes a detour around the Vice Chancellor’s garden (I don’t drive to work, so the detour got to be annoying – it may be fixed soon as they finish the health campus extension). Since 1981 it has changed a lot with many new buildings. The ducks are still everywhere. The central, rather bland, concrete Alex Square, is still the heart of the campus but the number and quality of buildings has increased considerably including a centre devoted to the life and work of John Ruskin, an information technology centre with a restaurant that has a nice southerly view, a wooden creative design building (LICA), and new residence halls. There is a wind turbine on top of the hill, the other side of the M6. The ‘spine’ linking the buildings was the subject of a drawn-out rebuilding project in 2017-18, finally looking better when done but the project was agonising to experience with up to 12,000 people trying to get to classes and meetings via detours. The reputation of the university is good, one of the top 20 in the UK by most measures. Although it is a ‘research university’ by any standard, the focus on undergraduate teaching is equal or in reality, greater, particularly because this pays most of the bills, especially since student fees were instituted in the UK replacing government block grants [the current full fees started in 2012–13]. The university seemed affable and welcoming, especially viewed against the larger and rather more elite institution I had been at in Australia. By the time I finished the interview and arrived back home again, I was offered the Lancaster job. This was a great surprise and my family and we talked about it at length. In the end, my desire to round out a long-ish career as full professor, in a tailored role in my field (political ecology), got the better of me and I accepted the offer. The family committed to one year in Lancaster, after my wife visited with me in mid 2016. With elderly parents and other relatives in the UK, I saw this fulfilling personal and professional aims. I set off from Melbourne with great hope in January 2017, on my own, straight into teaching.

Decades (actually, 17 years) away from a regular job in the UK had not prepared me for this return to the country. Many things were familiar [the supermarkets, the high train fares, regional accents that change about every 60km, decent newspapers and radio, M&S with its nice prepared food in hard plastic containers]. But now the nation was paralysed by Brexit, of which more later. I had also forgotten, or chosen to forget (from my 8 years spent teaching in British universities long ago) the numerous ‘systems’ now controlling teaching and research. Other differences: in my previous roles in the UK, based in London at two universities, I was at a different stage of life. I had been pretty successful with publications and grants, and I was a popular teacher. I was in my 30s then, had plenty of energy, no children, and was unmarried. I held simultaneous research grants in remote West Africa and in London while also completing a PhD in the first years. While at Brunel and the LSE I lived in Ealing and Harrow, and became quite involved in the local community. National research and teaching audit exercises had barely entered higher education back then. The degradation of pay, against rising cost of living that everybody experiences in the UK universities today, had not yet set in. Payments into a university pension plan were secure [they are less so, now and there was a 14 day national strike about this in 2018].

Arriving in Lancaster so many years later, many things were different in the university environment, aside from the geography. I was older, for one thing, and I had to learn on the job. This was not a huge hardship, but it did provide interesting comparisons. Fortunately my initial work obligation was teaching a class where I could largely build on what I had been doing in Melbourne, so rewriting lectures was manageable. This cannot be a discussion of my views of working conditions, but the strangest thing (to me), was that I was not allowed to completely manage my own teaching, even as a new Professor and head of a research group and with 26 years of teaching experience. Teaching was controlled by people on two teaching committees and by a number of rules. I was very used to directing my own syllabus, assessments, and sometimes asking students what content that would like to add to a class, at the beginning of the semester. No such luck in the UK. For my own class I had to use last year’s agreed assessments set by a different lecturer. Assessment included an exam. I was horrified: I do not use exams. They freak out the students, make grading drag on into the summer break, and test what you can put down in two essays in two hours from a short list of questions vetted by other lecturers. Not until the third year of teaching this class could I get all of this changed, which the students of course appreciated. I should say that the British lecturers found all this quite normal and it is because of university and national teaching quality measures that increased oversight of what lecturers get up to in recent years [although with some negative effects – odd ‘quality control’ and the financial imperatives seem to have led to too many 1sts and 2is given in the UK for example]. But it caused me sleepless nights.

On arrival I was very kindly lent a flat in the Castle Hill area, struggled to learn the various online teaching management packages that were completely new to me, and tried my best to settle into a totally new environment with two bags of belongings and a folding bike. In February I moved into a strange flat in Greaves Park which had nice high ceilings, in the back of an 1840s country house, which is used as offices (pic.).

Parkfield Lodge, Greaves Park, Lancaster. [driveway] I lived in a flat on the right. Entire large building sold for £320,000 in 2018! Housing is cheap.

This was February and it was freezing cold. Using my bike, I set about trying to find some furniture. I never found the right shops – ending up in Morecambe Market, where Steve sorted me out. The Market is an emblem for Austerity Britain- the

food stall selling out-of-date stuff is a treasure. I only discovered the secondhand furniture places in Lancaster later. It was pretty cold and two months later I was still barricaded in my bedroom with the radiators on, watching moisture drip down the back wall. Thermal inefficiency, not great when you are an environmental researcher.

At work, I gradually got the measure of the huge department I was in. I already knew, geography [my original discipline] had been folded into a wider entity, some years ago. This had occasioned a few retirements or resignations but it became part of one of the largest environmental centres in Europe, which is a good thing, as well as the largest department at the University. In 2017 many of the new colleagues were friendly, but not so much among most of the natural scientists and their students. They were not unfriendly, but we just had little in common academically and some of them had been there for years already, and had their own networks. This is a classic problem in universities, and I am a lapsed/non-scientist, on the other side of CP Snow’s ‘two cultures‘.

A digression on working in interdisciplinary settings. Lancaster operates a campus in Accra, Ghana and there was a lot of research and teaching taking place there, before and after I arrived. I am not a well known researcher on African cropping systems, but I do have years of research in West African rural communities, from a PhD in Burkina and ran a big research project in Niger. These led me to be pretty sceptical about the import of Western agritech innovations, like new crop varieties, to Africa without considerable forethought and with input from farmers. These might produce more crop yield in the lab, and some under field conditions, but as the anthropologist Paul Richards reminds us, they rarely adapt well to the social and economic environment of a semi-subsistence African village, where labour requirements, social norms, indigenous innovation, and gender relations determine what can be grown and where, in varying micro-environments. Those issues and behaviours have been developed over centuries, are quite remarkable, and exist despite constraints on crop production being considerable. Changing photosensitivity or improved pest resistance of plants bred in modern labs is essentially unimportant for farmers if the crop does not fit within local labour patterns and gender relations. Painstaking research is needed to work out these contexts – we could call it ‘technography’ as Richards does, or ‘Agricultural Innovation Systems (AIS) thinking’ as others do, or the ‘political ecology of agriculture’. It should be part of trialling every scientific innovation but it is often skipped, scanted or deemed to be somebody else’s job. I have spent much of my research career illustrating how much better farmers are at managing harsh environments, than some scientists give them credit for, following the work of Mike Mortimore and others. I also challenge another myth – what Andy Stirling calls ‘incumbent’ approaches to innovation. We don’t have a ‘food security crisis’ if our global food surpluses were better distributed – it’s an access to food question in the countries I know, not a ‘need to produce more’ problem at this stage, assuming good distribution and overcoming power inequalities [a big problem to work on]. Agribusiness is not necessarily the friend of the poor and vulnerable, either, and ag science often supports commercial operators de-facto without delving into this issue. Agribusinesses can afford to buy seeds, and take over land, better than semi-subsistence farmers.

I know, and I found, this type of talk is not popular among plant biologists, of the type that don’t consider such ethical issues or do such fieldwork. Why a failure to engage with basic and proven issues that determine whether lab research will be taken up? Or, why not follow through how seeds and plants are actually absorbed into and used in social systems? The failure to consider this point upset me on a few occasions – eg presenting to a less than sympathetic audience at an N8 AgriFood meeting. And again when I was not invited to particularly crucial meetings in my department-lots of other junior and senior people were. I’m not much of a lone worker, able to be head down and ignoring what is going on down the corridor, and a lot of it was plant biology. I probably needed, if I had stayed around longer, to try to rescue my situation by securing funding for work on agricultural innovations that crossed from seeds to people and into the important social questions. But I guess none of this would have been well received.

Really, just different priorities and philosophies at play. The problem of finding like-minded people was not insurmountable since the Dept. also contained some friendly people including some stellar social scientists, with a different social circle. And, a good group of those across campus in other departments – Lancaster was the home of John Urry who founded the Mobilities Paradigm [he sadly passed away before I arrived], Brian Wynne, and Andrew Sayer and Bob Jessop are still teaching. The Institute for Social Futures, established by Urry, still meets regularly and has core support. It’s not so big on the sort of work I do, but every university should have something similar. When I joined Lancaster I soon realised our particular grouping on political ecology was better known outside the university than within [and our teaching was popular]. In debate about planetary and environmental matters in the UK, we were often listened to, but in internal university issues, less so. Investment in hiring me [and appointing a successor in 2019], as well as some internal promotions and successes, were welcome exceptions to this. But I was hired in part to introduce some change and to raise the profile of social sciences in the light of various environmental emergencies. Sadly I am not sure I really managed that, for research or for teaching.

Regular life for me in Lancaster revolved around very hard work in term time, less so in the vacations but still full time. On research, there were plenty of grants to apply for, more than when I left the UK in 2001, but unfortunately none of my/our applications were successful [long story – one was, apparently but without me, and another I had to leave and it later won E1.3m!]. I went to Ghana to start some new work on supporting small farmers – first time back in West Africa since 2001- and spent a lot of time editing work for the Journal of Political Ecology , writing, and helping on other tasks including managing the Lancaster Political Ecology research group and a lot of refereeing of articles, assessing job candidates, PhDs and promotions. Some of this took me to London, Cambridge, Switzerland, Austria and the Netherlands, and I felt like a real European academic for the first time in decades. That was one of the attractions of leaving my comfortable 10sq km of Melbourne – to treat Lancaster as a European town.

I spent all but one year in the city on my own. I moved house once, to a small terraced house with a less than helpful landlord, when the building in Greaves Park was repossessed and changed hands. I went into town every day, and discovered three places to hang around and eat and drink coffee – the Hall [in an old chapel with distressed chic features, and quite high-end for Lancaster], the Whale Tail vegetarian café above the organic shop, Single Step, and Roots Café, which did not survive into 2019. Brew Cafe was doing well when I left. Paul from Brittany sold his crépes in the market and provided French conversation. Having visited one place or the other, there was shopping to do at the twice weekly market or a supermarket, and some cycling – to the seafront at Morecambe for example. The Bowland Fells behind the town to the East defeated me on my small folding bike. I did not have all that much else to do in town. Staff at the university had their social networks and much younger families too. Some lived further afield. I also spent many weekends visiting my elderly parents elsewhere in the UK, travelling for up to 6 hours each way to do so.

I should have helped out at the local community farm, but somehow never got there. I did not participate much in three of the local pastimes – going to the pub [almost never, as a non-drinker], going Fell walking [almost never, and when I did, I fell and cracked a rib], and I have never taken any interest in supporting sports of any sort. I remember hearing shouting coming from up and down the street in 2018, and realised England was playing a crucial game in the World Cup. The sports thing was a conscious decision when starting out as an academic, trying to save time for other activities, and it has proven resistant to change except when my son is competing. He was not there initially. I was not in any school social networks until we established those between Sept 2017-18 at the Lancaster Royal Grammar School.

The townsfolk were diverse in some ways, not in others. The Lancastrians had grown up in the place, had distinct Lancastrian accents, and could handle the [often dreadful] weather and enjoyed the local culture. Of course they are a diverse bunch of people, but all are linked into social networks and local places. They complained a little less than the in-movers like me about various meteorological and economic issues. For example when rain or ice makes outdoor tennis at the club impossible, they travel 30km to Preston to play indoors! Between Lancaster proper and Morecambe across the river, the data show majority Conservative voters [Morecambe side] and majority Labour [Lancaster] even though Morecambe is much poorer. The views about Brexit are generally, but not exclusively, divided along the same political lines, despite Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn’s well known dislike of Europe. I discuss the stats below, but they need a finer-grained analysis. A widely quoted statistic is that Lancaster is 94-95% white, confirmed by the latest census from 2011. But there was certainly an important girl’s Islamic school and some people of colour, although few in the general population. There was a particular subgroup of local residents, progressive in their political and social opinions, with which I had affinity. They worked in various social roles, including at a community farm, as Quakers, in local NGOs and associations, in support to refugees and with asylum seekers. Great people and many chose to live in Lancaster. Just up the river in Halton is a communal housing project of some renown that has 5* energy rated housing, and generates electricity via a weir and solar. I joined a small project fixing up used bikes for refugees in Lancaster – this proved successful and rewarding, and we met right through the dark winter months to restore and mend bicycles for people that needed them. I have done a fair bit of research on such altruistic things before and since, and it was nice to connect to this initiative.

It was apparent after 6 months in Lancaster that political divisions were founded in part on basic economic differences – although nobody from Lancaster would say they were any worse off in terms of class or income divisions than other northern British towns, I suspect. The presence of two universities, and a large hospital meant several hundred or more highly skilled professional jobs. And 14,000 students with their spending power, present for about 8 months a year. As well as some local resentment towards them of course, among the majority non-university affiliated population.

There is much more to Lancaster – it has a small arts, music and theatre scene with decent venues. Campaigns on various social and environmental issues are frequent. And a few festivals. But the differences in political attitudes, levels of educational attainment, social class, and wealth were clear, and the unemployment rate high, particularly on the Morecambe side of the river [good article on Morecambe and Brexit, Nov 2019]. The political divisions were clear from the results of the various local and European elections I participated in during my time in the city. I had come from an inner Melbourne suburb with voting for the Greens above 25%, massive gentrification, and over-inflated property prices. Citizen activism was very high, and the population increasingly multicultural. In Lancaster, Greens only performed well in the local elections, and housing seemed extraordinary cheap. A good sized 3 bed house was much less than the price of a Melbourne studio flat. There was no gentrification at all that I could see, and plenty of vacancies on the High Street.

The culprit was ‘British austerity‘ which afflicted those reliant on any form of government support, and some not so reliant as well, as economic downturns also ate into retail spending, economic regeneration, etc. Austerity involved a dramatic and deliberate reduction in central government funding to local authorities and councils [the ‘local state’] after the global financial crisis of 2007-8, and this region was still struggling under this regime. Austerity was manifested as potholes in the local roads, zero budget for progressive infrastructure like bike lanes, no money to improve recycling [no recycling of plastic trays for example, even though there is a recycling plant elsewhere in Lancashire!], reductions in social services, and closed council-run public facilities [but the city museum and libraries did stay open]. Support for community endeavours had been reduced. Lancaster was by no means the worst – Morecambe has struggled economically for decades, as have other Lancashire towns like Fleetwood and Preston, and north into Cumbria. As an expat I had not really experienced austerity to this degree in a Western country. The last time I lived in the UK was in Wendover, Bucks for a few months in 2011 where it was not really so obvious in a wealthy village. During the GFC in 2007, I was also in the UK – as a Fellow at ECI, University of Oxford and I was given a flat, rent free and surrounded by wealth. And I grew up in London, somewhat shielded from the 1970s economic disputes and strikes. So I was ill prepared, and the state of the North in 2017 was certainly different.

Politically, the country and the region were convulsed by Brexit discussions. Virtually no British academics supported Brexit. We tend to be international in outlook, and anti- or certainly less nationalist than many. I found myself on my own at home, listening to Radio 4 and the evening roundup of news from Westminster, shouting with disbelief in the kitchen and into the woodland behind the house. It was truly unbelievable; the Conservative party betrayals, Machiavellian political manoeuvres, the abject failure of the opposition Labour Party to commit to a pro-Europe stance or a second referendum, and the continual trotting out of Brexit being the ‘will of the people’ – as if the majority of voters and non-voters had made a rational decision and had a clue at the time about multi-layered governance or economic realities and trade imbalances. The conflation between Conservative party politics, as they still selfishly seek to make sure they are electable, and the life-and nation-changing Brexit decision, is agonising. As I write [2019], there has been no advancement of the UK leaving the EU, the only credible plan having been formulated by Theresa May who is no longer Prime Minister, ousted by her own party, with her deal rejected three times in the Commons. Brussels dug its heels in. The virulent ‘leavers’ like Boris Johnson – now Prime Minister and an untrustworthy erratic right wing nationalist who just suspended parliament to avoid dissent – and Naab, I have no time for at all. I have no faith that the UK will survive fine without the EU, and the economists tell us it will not. Symbolically, the efforts to leave the EU and claim ‘sovereignty’ appear to me to be, in reality, xenophobic nationalism, and the referendum in 2016 saw many voting ‘out’ on Europe only because they were opposed to David Cameron’s form of conservatism and the poor living conditions they were suffering under Austerity. Many of these being working class people without any or with few ties to continental Europe. They made their vote for Brexit one of protest about existing conditions in the UK, which were particularly bad outside the major metropolitan areas [which all voted to Remain] and certainly across much of Northern England. [However in numerical terms, Brexit was won by older and richer Southerners, Prof. Danny Dorling suggests]

As a student of New Caledonian politics in the francophone Pacific, I knew something about referendums on independence. These islands have three chances to vote on full independence from France, not just one [the first vote in 2018 resulted in a decision to remain with France, but by quite a small margin]. This is clearly what the UK needed – more than one try, or a different flagfall percentage. In sum, being in a small city with a strong regional identity and quite a considerable Brexit vote [Lancaster city probably voted Remain but just, although lumped in with Fleetwood – constituency vote was 51% leave, but Morecambe and Lunesdale 58% leave] gave me an appreciation of political events that I would not have got in London or the economically dominant South East. It also made me resentful. I got to hear long diatribes about Europe and what it was costing Britain – from people who had scarcely been across the Channel. Claims of ‘immigrants’ taking jobs, must have referred to the small numbers of Polish, Eastern Europeans including Albanians and Romanians, Turks, and others who have settled in the region (in the last census, Lancaster had around 8-9% born outside the UK, but that would include Ireland and other Northern Europeans and some transitory students). There were 2 Polish shops in Lancaster, then 1 by 2018 [perhaps reflecting departures]. This was not a region of mass immigration. So none of the rants made much sense to me. There were, anyway, few jobs in the region that a recent immigrant could take.

When my son went to LRGS we found it was the school that my wife’s father had attended in the 1930s [he left to Naval College, and became a young Naval Commander at the end of WWII]. In national terms LRGS is very good state school for able students [and free]. It is not an ‘alternative’ type of school. Several students from diverse backgrounds make it on to top universities like Oxford and Cambridge if they want to, there is a lot of after-school activity in sport and music, and a range of pupils including some from wealthier backgrounds. The boarding facilities are for students from out of the catchment, some from other countries, and they pay a boarding fee. In 2019 it became co-ed in the 6th form. Families relocate to its catchment area and also for the Girl’s Grammar School down the hill in town. My son, once he got over the shock of wearing a uniform and the stricter school regime than in Australia, performed in music events, as well as sport and rugby in particular. The rugby teacher assumed he could play rugby because of his build and Australian background – but actually there is almost no rugby in Melbourne, which is an AFL city and the home of that game! Rugby matches were sometimes cancelled at LRGS because of ‘frozen ground’ – schools do not compete when the pitch is actually frozen, and this was a real problem in the winter of 2017-18. His rugby team came second in the region and he did very well in athletics, once boarding a coach for what he thought was a trip to a local competition, not knowing place names, and ending up competing and winning in Gateshead several hours drive away near Newcastle. Had we stayed, I think he would have remained at the school, and probably done well.

My wife and I attended, at various times, adult education classes in French, and choirs, opening up new avenues. No complaints there, and we made some friends along the way. We also visited my wife’s relatives, in Bridlington, York and the south east, and entertained a few visitors, one of whom, her cousin, took to Lancaster and came several times. But in late 2018 my small family had left again for good, and gone back to Melbourne. My son wanted to complete high school in Australia where the majority of his friends were, and my wife had had enough of the cold and wet winters [they really got her down], and could not find any work. They do not do ‘spousal hires’ in UK universities, at least not at Lancaster. The reasoning is that the country is small enough to find work elsewhere. But in reality Lancaster was too far from major sources of jobs except Manchester, and she had tried three times in my Department for positions where she was extremely well qualified, but was unsuccessful, for unknown reasons. This is the reason some universities, in the US for example, offer meaningful assistance to spouses and partners looking for work. But maybe that is only for the ‘superstars’ in the UK. Finally I decided in early 2019, with all of this going on, I would return to Melbourne, taking a demotion to do so – a highly unusual thing among academics, who almost universally aim for promotions to full professor if they possibly can – the top position symbolically and in terms of pay and stability. I am not expecting any sympathy here, but ‘job vs. family’ decisions can be hard.

I sold up what I could of my belongings in May 2019, and gradually emptied the house over a month, with many useful and saleable things going to the local charity hospice shop or the council collection scheme. So a lot of stuff was recycled into the local economy. A hybrid Honda went to a relative. Nine sacks of stuff I could not rehouse were left outside for the bin men when I closed the door and posted the key through the letterbox. I left with my two bags at the end of May, having worked really hard to complete all the teaching and administrative parts of the job. I actually spent a huge amount of time on this in the last few months, and taught a lot too. I taught only about 240 students in my time there, but I found the majority to be willing to learn, and a few have been in touch since.

General thoughts

Lancaster is a good town. It is cheap to live in by British standards, you can walk to all services – shops, doctor, sports facilities, and so-on. It has most of what people need, despite many vacant shop fronts. It has the best arts and music in the region. The countryside around, if you are interested in that, is very beautiful, although often wet and cold. Houses are cheap. You can be in the Lake District in 40 mins by train or car, and see it from the top of the town every day. But this is not a cosmopolitan, metropolitan place as I was more used to. I am very happy [for the people of Lancaster] that there are 2 universities there. This increases the human diversity, spending power, the range of cultures, and ideas and human capital. When the students are not around in summer for example, the town is much poorer for it. And there is a population of refugees and asylum seekers, several of whom I got to know and who exist in a liminal state of uncertainty and without enough resources. They are supported, although less by the government in Westminster than by compassionate organisations and local people.

It has a culture that is ‘northern’ – this is hard to capture. My grandparents were ‘northern’ but chose to leave the region so I never grew up there: although most of my wife’s family identify with the North or were born there. People are less ‘precious’ than in more affluent parts of the UK, generally less wealthy [although not so in cities like York and Harrogate], and perhaps more stoical – a useful characteristic as the UK self-destructs under appalling self-centered leadership and political infighting and as it hurtles towards economic disaster by leaving Europe. There is a definite scepticism about London’s dominance of almost everything. Lancaster takes some work to settle into, as an outsider with absolutely no existing contacts, and I found I would need a few more years – partly because I worked in an environment where you had to build up your own networks – which I was expected to do in the office environment since I was actually a Professor and head of a group. And partly because I am not from the North-West – in my life I had never even been to Blackpool, once one of the the country’s greatest holiday resorts, and I had been to Manchester, the nearest big city, only twice! I realised the community work I did, with the bike project, largely involved working with people who were born and raised somewhere else and with broad horizons. At the university, almost everybody I got to know came from somewhere else .

As for British universities, of course ones like Lancaster are world standard and do very well – I think Lancaster is in the world top 150 in most ‘rankings’, whatever they are based on. Its teaching is much better than richer and more prestigious British universities, as recognised in various national surveys [in 2018 it was awarded a Gold teaching award, unlike some much more established institutions]. The students wrote much better essays than at the University of Melbourne where I teach a very similar 3rd year class. But this is achieved by a truly enormous amount of hard work by the teaching/research staff, that in some departments and disciplines, is not sustainable and not always that enjoyable, partly because it is over-managed [Prof Ailsa Henderson on this point for University of Edinburgh here – give us back our authority!] and time-consuming for some [my own teaching was do-able, at least when the family were not with me]. British academics and their managers blame the government for progressively winding back support to higher education ever since the time of Mrs Thatcher’s attack on the sector [she removed tenure, for example]. And for making them compete with each other for students. Students blame the government and the universities for instituting high compulsory student fees of over £9,000 a year. There is no way that academic’s pay has kept pace with the cost of living, although somewhat miraculously, most Lancaster academics can actually afford to buy a house on their salaries, which cannot be said for many other parts of the UK.

Although my job was almost manageable in a 40 hour week [OK let’s call it 50], my particular gripe is with metrics and markets entering university life – and these are shared with Australia where I have written about higher education. It is easy, faced with ‘quality of teaching’ and ‘quality of research’ assessment exercises, pressure to recruit students and turn around huge loads of marking, to forget about what academic jobs are really supposed to be about – ideas, invention, passion, knowledge, imparting information and skills and wisdom, in my case social and environmental justice, and ‘affirmative’ research. Not trying and failing to publish in ‘4 star’ journal outlets, maximising journal citations, preparing for the national REF and the TQF etc., fighting for grant money, getting promoted very quickly, and dancing to the metrics of an audit culture. This mentality places an emphasis on staff performance, rather than staff satisfaction; it leads to competition between institutions instead of cooperation; and it ends up making many people miserable. My employers did try to reduce the effects of the metrification of academic life, within the budget constraint of needing to keep up the hours devoted to teaching and student support and committee work. They still valued ‘research grant income overheads’ from grants very highly [I won none, so I got no reduction in workload to compensate – only 20% of my time was officially allocated for research in 2018-9!], and there was stereotypical praise of course for ‘publishing in Science and Nature‘, the two top science journals in the world. The social scientists were deeply cynical about this sort of thing. I have often argued that there should be university prizes for conducting research with no funding at all, and for publishing ethically, which means in outlets that are free of corporate control and open access to the public. I think many colleagues in science thought I was, quite simply, crazy on these two points.

My thoughts on ‘belonging’ more generally, having not really found a place in Lancaster, should probably to be told another time. I will not say anything more about the highs and lows of the place. Even if you contact me. There are really no answers to what makes people belong in a place. Elsewhere on this blog I have already told of my dissatisfaction with where I grew up, and where I went to university. I was also happy to leave the US, where I lived for about 8 years in total. I left West Africa early in 1993, because I was quite ill – I would have stayed longer. I loved Brussels. And West London, but I can’t manage the air pollution in London’s city centre anymore.

I arrived back in Melbourne in June 2019. I might just ‘belong’ there the most, and I managed to get my old job back, but not under better conditions than when I left. I returned with some misgivings. I hold Australian citizenship and can vote, but I am not proud of the country’s leadership, general intolerance, environmental record, and its reliance on exploiting its natural resources [JM Coetzee on Australia’s Shame]. Its public universities are hardly that anymore. Melbourne is a growing, expensive global city of 4m. I did not leave Lancaster on a sour note, and former colleagues were supportive. My job was re-advertised and has apparently been filled. The fate of the nation, Led By Donkeys [worth clicking] in which the university and the town sits, however, is currently hanging in the balance.

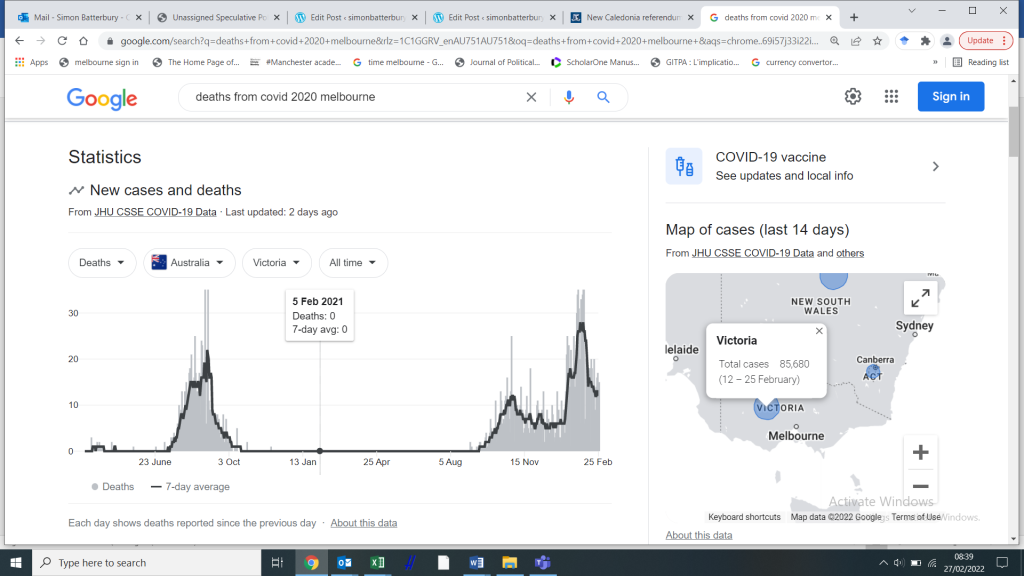

2020: and then there was Covid-19….British mismanagement of Covid, many deaths….furloughs and financial problems at both universities due to lack of International students….

March 2022: I managed to return for three days on a nice spring day with no rain. The haunts are still there, the bike project is still running, there is a new bike path across campus and more construction projects, and a new town is planned right close to the university. The town centre and campus now has its students back.

It was clear that work needed to be done. Parts of the campus are old. Alex Square, in the middle, was already repaved and fixed up some years ago , but the walkways connecting to it had not been.[we would still like our bike racks back outside the library – nowhere to park one!]

It was clear that work needed to be done. Parts of the campus are old. Alex Square, in the middle, was already repaved and fixed up some years ago , but the walkways connecting to it had not been.[we would still like our bike racks back outside the library – nowhere to park one!]